In nature, there is an order that emerges from apparent chaos. What seems random follows simple rules that, when combined, create organized systems without anyone directing them. This type of behavior has inspired mathematical models that attempt to imitate and understand how this harmony arises.

Thousands of birds move as a single body, avoiding collisions and generating undulating patterns. Each one adjusts its movement according to the position and velocity of its neighbors, obeying only local laws.

Schools of fish show similar behavior: each fish responds to basic forces of attraction, repulsion, and alignment, forming fluid structures that adapt to the environment. This collective coordination is a clear example of emergent intelligence.

Sunflower seeds grow in a spiral following the golden ratio . Each new seed is placed at a constant angle from the previous one (approximately ), so they fill the space without overlapping.

But why are all these behaviors ordered? What is the reason for being this way? We rarely stop to think about the utility of these patterns because we coexist with them daily. However, if we observe carefully, we find a beauty in nature similar to that which inspired James Kennedy, a social psychologist who studied the movements of birds in flocks. He discovered that their social behavior followed patterns that allowed them, collectively, to find food and survive. This principle also manifests in other living beings, even in humans when we work in groups.

James Kennedy, together with Russell Eberhart, understood that this collective behavior allowed birds to optimize their goals in any space. Thus, they modeled an optimization algorithm called Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), in which the particles of the swarm seek to optimize a function. This algorithm was a success: by imitating the social and cognitive behavior of birds, it could be applied to mathematical optimization problems, even surpassing differential methods in certain cases, and efficiently exploring high-dimensional spaces.

PSO Algorithm Description

(The code is at the end)

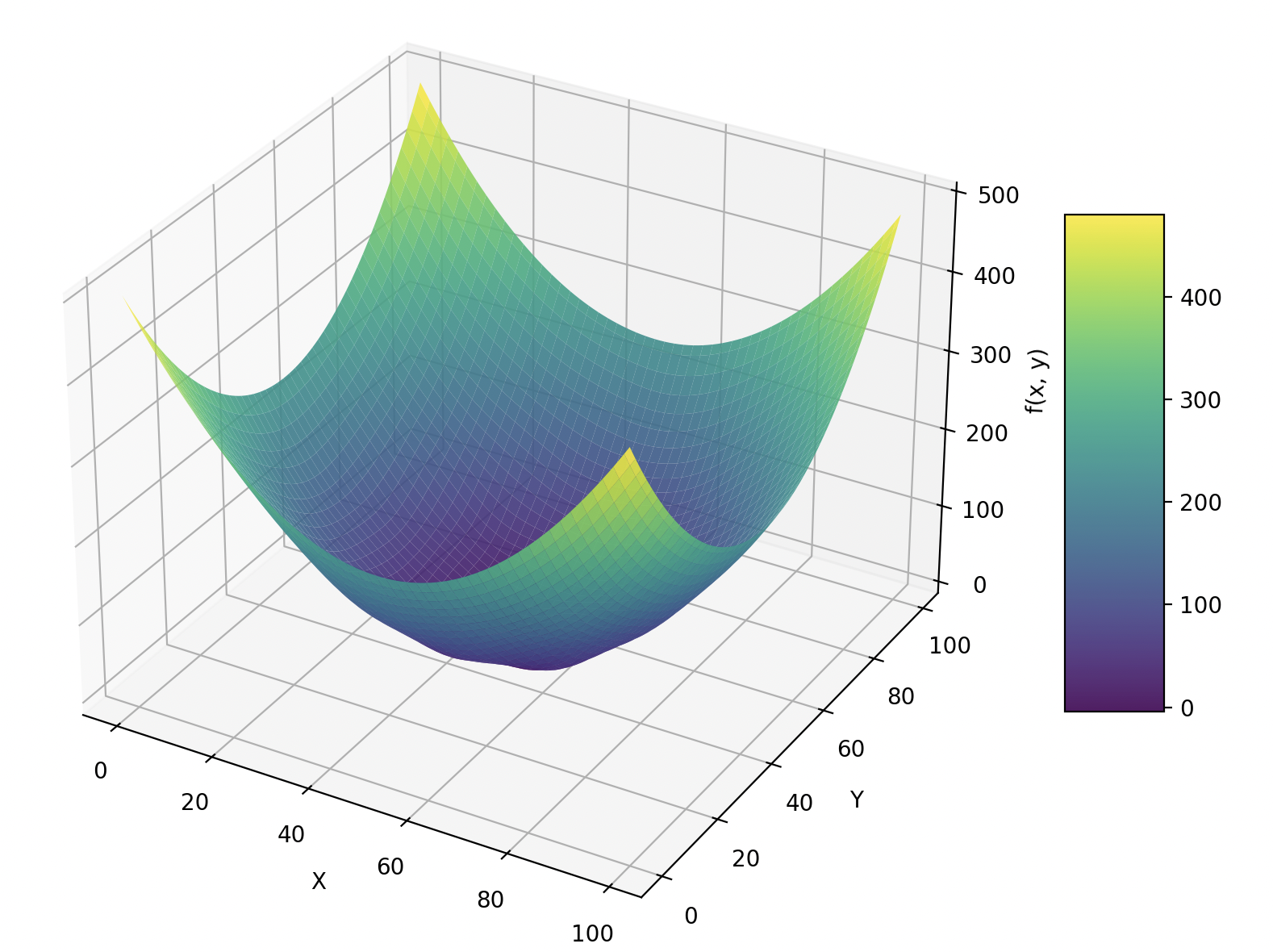

The goal is simple: given an objective function, we want to minimize or maximize its value.

In other words, we seek the values of the domain that produce the smallest or largest result. In this explanation, we will use the minimization formulation:

We define the following variables:

- : the search space, the field where particles can explore.

- : the number of particles.

- : the current positions of the particles.

- : the velocities of the particles, generated randomly at the start.

- : the best positions found by each particle (initially ).

- : the best global value found among all particles.

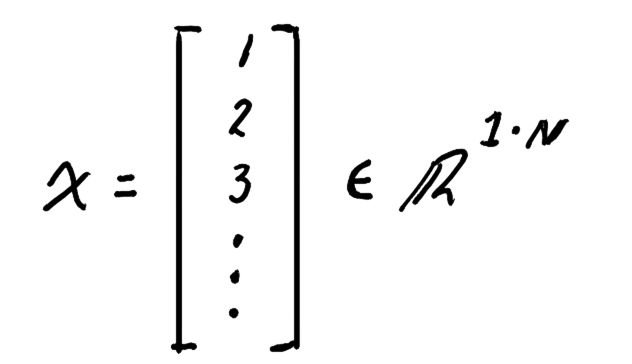

The positions are represented in a matrix of , where is the number of dimensions and is the number of particles. Similarly, the velocities have the same shape and are initialized with random values:

These initial conditions allow the particles to cover the entire search space, encouraging exploration from the start.

Then we repeat until updating (or until meeting the stopping criterion):

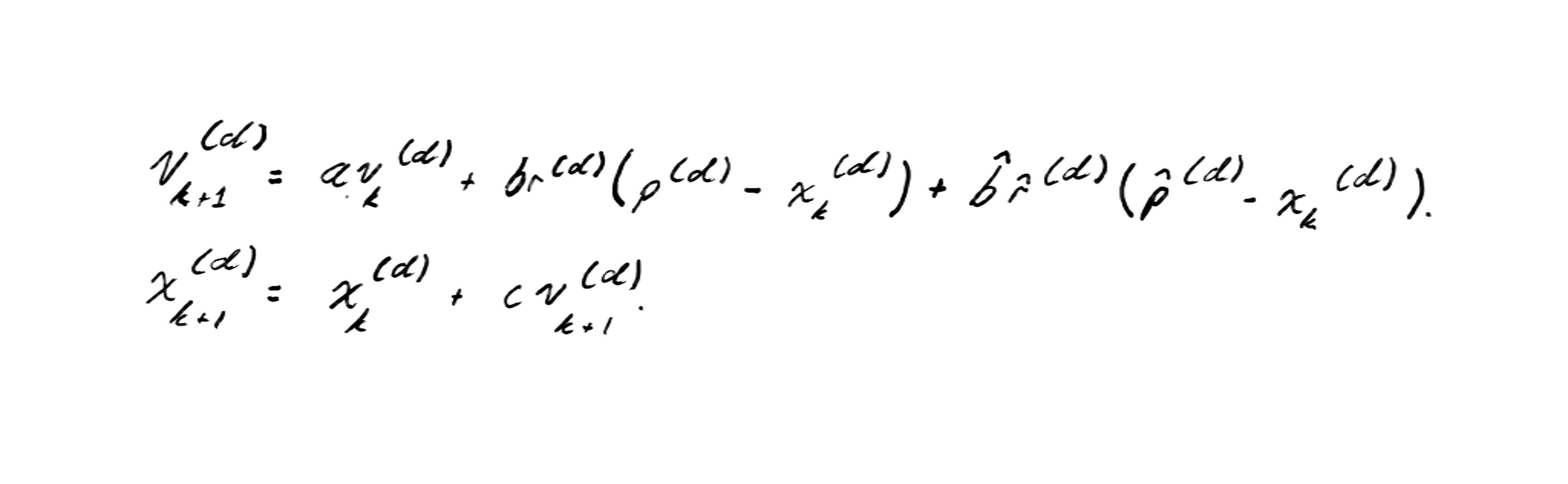

The velocity update is the heart of the algorithm:

We want to update the velocities before moving the particles, because this way each one "decides" where to move based on current information. This happens before the position change, since at the start of the algorithm each particle already has an initial position and knows both its best personal position and the best global value . With that data, each particle can adjust its direction of movement.

The term is known as the cognitive component.

It represents the particle's own experience, its memory. Each particle remembers where it has found a better value and, naturally, tends to return there. In a way, it is its "individual intuition": the force that drives it to explore again areas where it has done well.

On the other hand, corresponds to the social component.

Here collective influence comes into play. Each particle observes the best result found by the entire group and is attracted toward that direction. This term models cooperation: each particle learns not only from itself, but from the success of others.

The sum of these two components makes the swarm behave in a balanced way: the cognitive component encourages local exploration, while the social one drives global exploitation.

The result is a dynamic system where each particle alternates between following its own judgment and aligning with the group, a key balance for the algorithm to find the global minimum without getting trapped in partial solutions.

Randomness

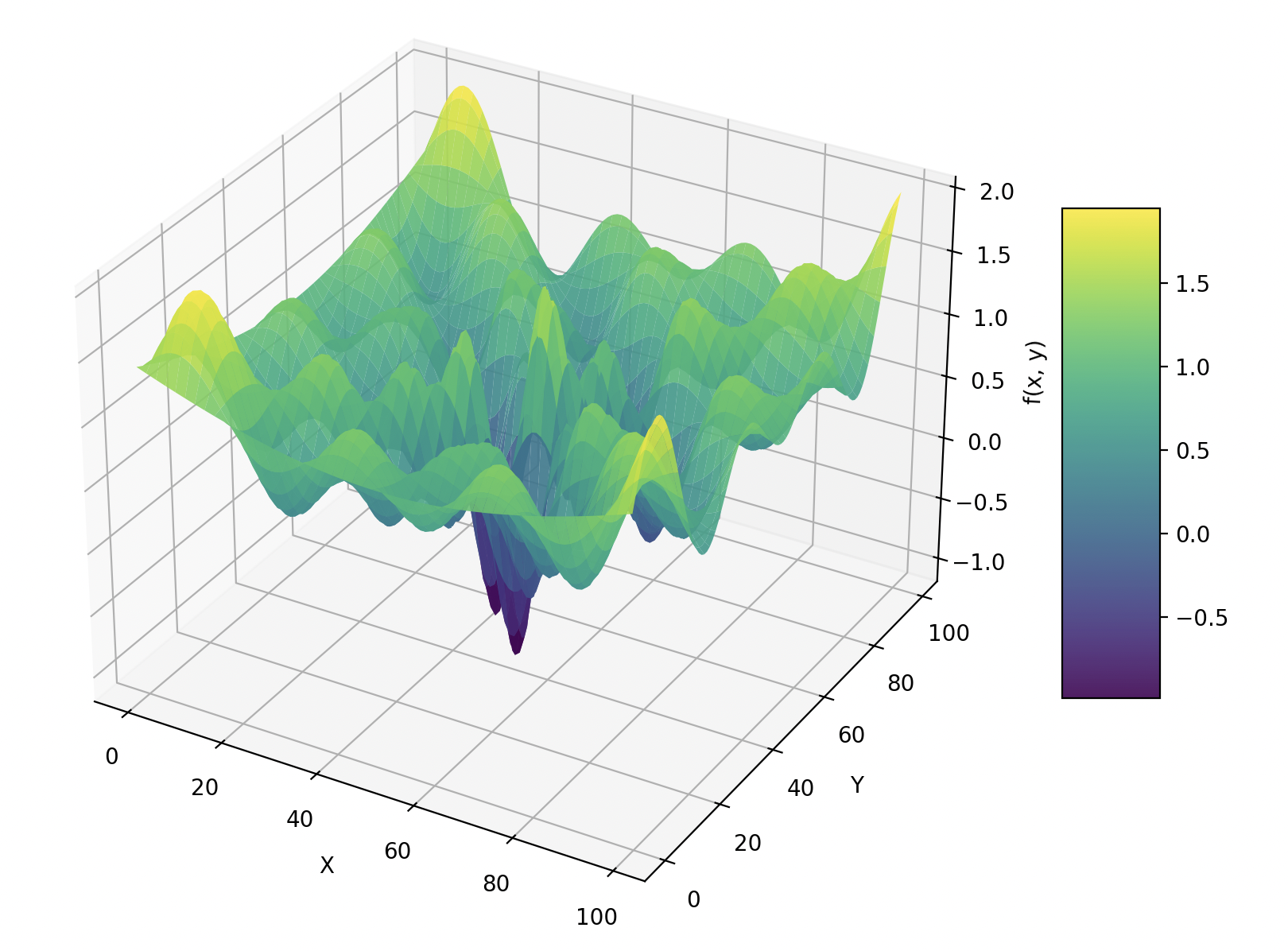

But all this has a problem: particles can converge too quickly toward a point , without having explored the search space sufficiently.

This can lead to getting trapped in local minima, losing the opportunity to find the best global result.

To avoid this, we introduce a new element: randomness.

The idea is simple: add a stochastic component that forces particles to keep exploring. Thus, the velocity update equation becomes:

where and are uniform distributions with the form . Each component satisfies .

Many authors present and as scalars, which is simpler but less flexible. If we treat them as matrices, each particle has its own randomness factor, independent of the others. This improves the swarm's exploration capacity, especially in high-dimensional spaces or functions with many local minima.

PSO is a weighted sum of social and cognitive components, but randomness gives life to the swarm, maintaining the balance between exploration and exploitation.

In more detail, if we analyze each component of the update, the main objective is that the positions are attracted toward the known best local value.

In terms of vector geometry, the vector represents the direction and distance that separates the particle from its best position. The sign indicates the direction of movement, while the magnitude indicates how far is from .

However, we don't want particles to move exactly to .

If that happened, the algorithm's exploration capacity would be lost. For this reason, we introduce the random factor , which makes the model become a stochastic system: particles move in a slightly unpredictable way, exploring new areas of the search space.

As an interesting fact, the original PSO paper (1995) was not born as a mathematical optimization work, but as a study on social influence and collective behavior. The authors adapted that idea of social interaction, how individuals learn from each other, to build a model capable of optimizing numerical functions.

But something important is still missing.

Hyperparameters

The algorithm, as it stands, does not guarantee convergence.

Particles could oscillate indefinitely or even diverge if the parameters are not well controlled. So, how do we make the system converge?

For this, we introduce hyperparameters: scalar values that allow us to adjust the algorithm's behavior and study its stability.

These parameters modify the velocity update equation, so we can control the influence of the past, the individual, and the group.

With the hyperparameters incorporated, the equation becomes:

Where:

-

: is the inertia factor or momentum. It controls how much previous velocity each particle conserves. A high value makes particles maintain their momentum, while a low one decelerates them faster.

-

and : are the cognitive and social factors. They determine how much weight individual experience and group influence have, respectively. Adjusting these values changes the balance between exploration (searching for new minima) and exploitation (refining the current best solution).

-

: acts as a step factor (similar to learning rate in gradient descent). It controls how much positions are updated in each iteration: small values produce slower but stable convergences, while large values can cause excessive jumps and lose precision.

In the end, we are left with the following algorithm:

Repeat until meeting the stopping criterion:

Return:

This scheme shows the fundamental cycle of PSO:

- Random initialization of the search space.

- Update of velocities and positions using the cognitive, social, and inertial components.

- Evaluation and update of the best individual and global positions.

With each iteration, the swarm explores, learns, and coordinates to approach the best possible value of the objective function.

Next, we will analyze how to choose these hyperparameters to ensure that the algorithm converges mathematically, representing PSO as a linear dynamic model.

Convergence Analysis

Convergence analysis allows us to find the equilibrium point of the model. With this, we can determine which values of the hyperparameters make the system stable and the algorithm converge.

To begin, we simplify the system by decoupling the dimensions and analyzing it in a single one. This does not alter the validity of the model, since the components in different dimensions are independent of each other.

By reducing it to one dimension, the system's behavior becomes easier to study and visualize.

Each coordinate of the vector follows the same update dynamics, so we can understand the general system from a single axis.

When we say that dimensions are independent, we mean that there is no cross-multiplication between them; that is, terms like do not appear in the model. This allows us to analyze movement on a single axis without losing generality, simplifying the study of stability and convergence.

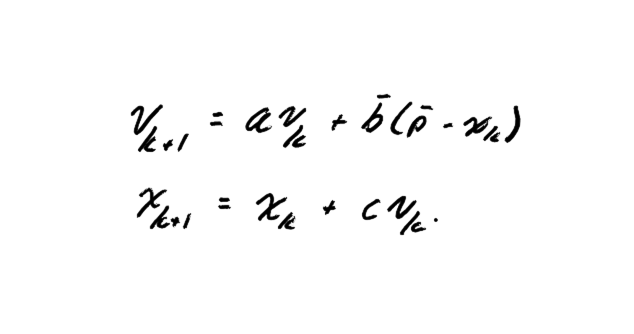

With this simplification, we can formulate the system in a single dimension as follows:

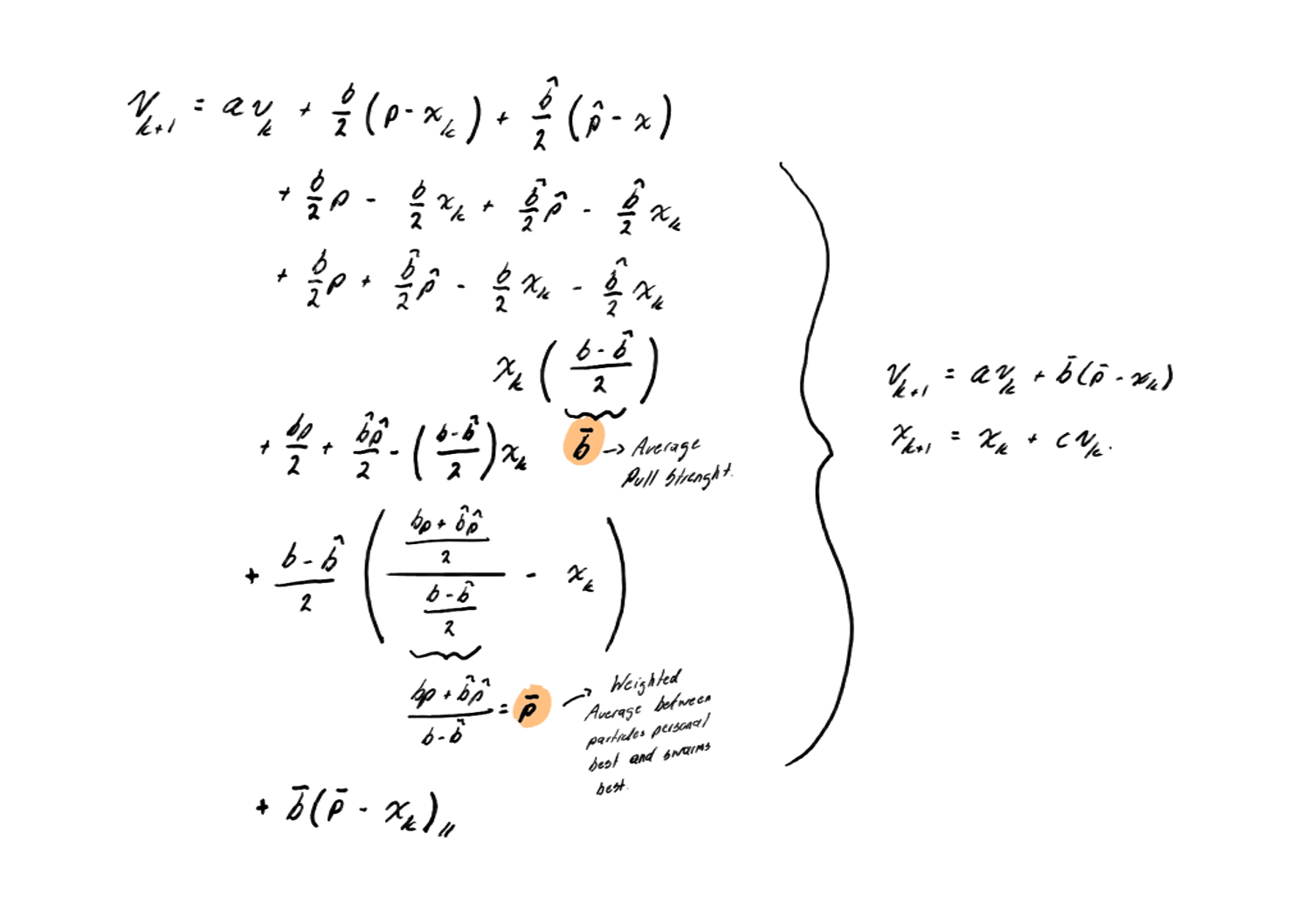

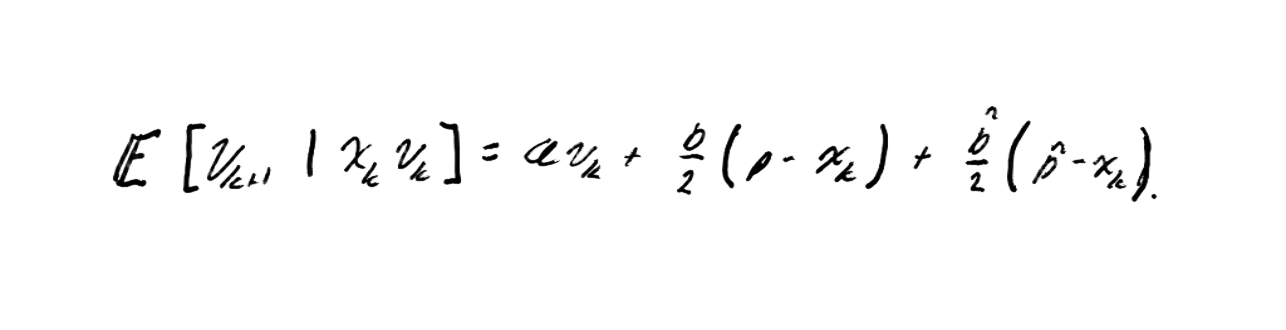

To analyze its stability, we replace the random variables and with their mean value. Since , both are uniform distributions and, therefore, their expected values are .

By doing this, we go from a stochastic model to a deterministic model, which allows us to study its behavior in a more controlled way.

This approximation is valid because the expected value describes the mean behavior of the system, known as the mean-field system. Although it does not completely capture random fluctuations, it is a solid representation of average behavior and is commonly used to analyze the stability of PSO.

Within this model, we define the average pull strength, which represents the average attraction force between particles toward their best individual positions and toward the best global value.

Combining both terms, we obtain a single resultant force , which acts as a weighted average between individual memory and collective influence.

Thus, the average velocity update (mean velocity update) is expressed as:

By transforming the stochastic system into a mean deterministic system, we obtain a linear dynamic model that we can study formally:

it allows us to calculate its eigenvalues, analyze its stability, and determine under what hyperparameter conditions the algorithm converges.

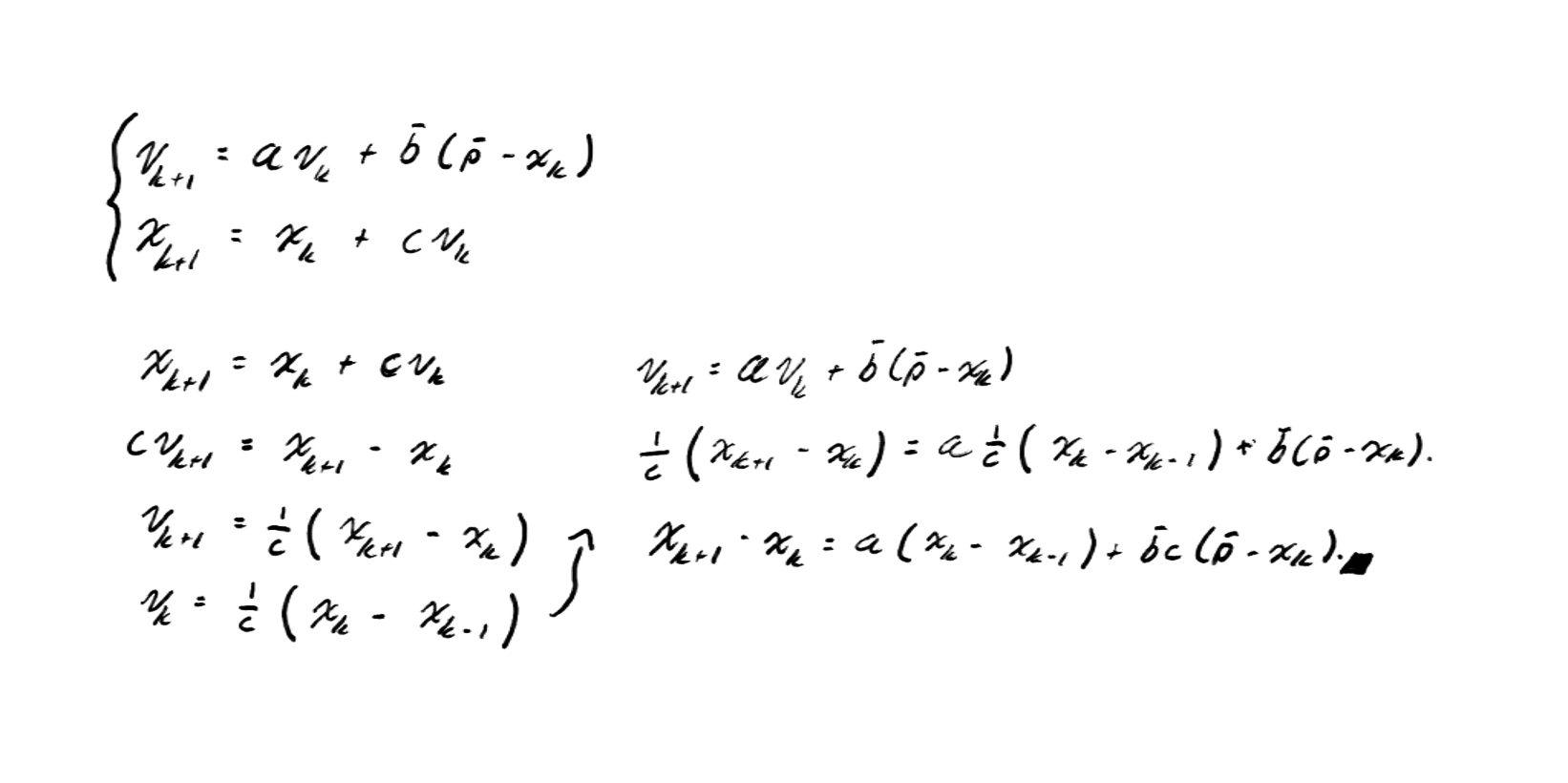

Our objective is to combine the two update equations (one for velocity and one for position) into a single one. This allows us to study the stability of the system more directly, since we reduce the evolutionary variables to a single variable .

In this way, we analyze how position changes over time without explicitly depending on velocity.

By doing this, we obtain a second-order recurrent system, which means that the next value depends on both the current value and the previous one .

This type of system gives us more information about dynamic behavior, because it incorporates the so-called momentum: the inertia of movement as a function of where the particle came from and where it is heading. In other words, to know where the particle will be next, we need to know where it is now and where it came from.

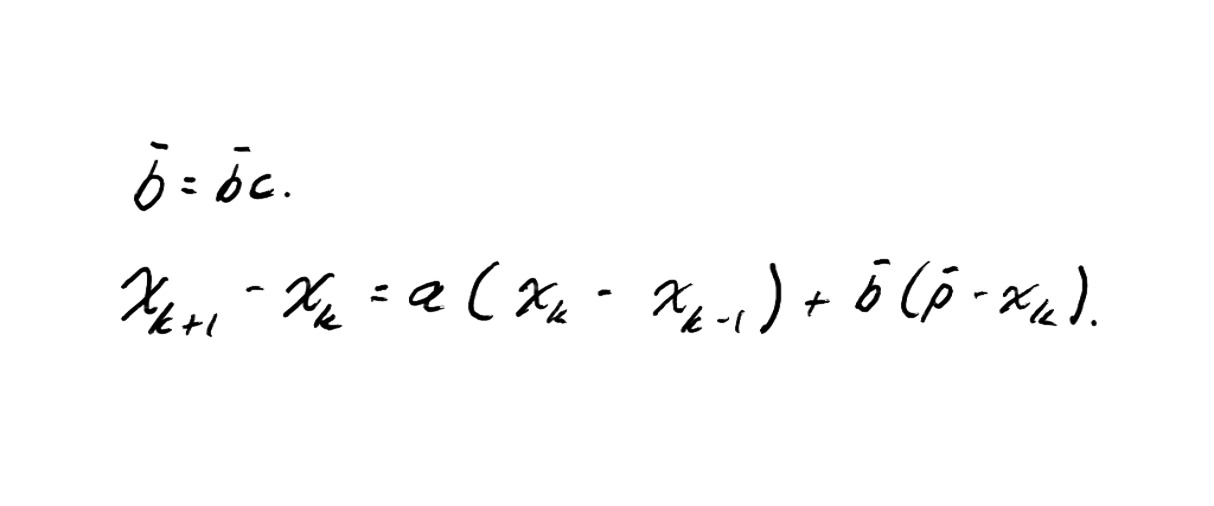

Additionally, we can simplify the analysis further by taking .

The parameter simply acts as a scaling factor in the attraction component. Removing this constant does not affect stability, it only changes the scale of the attraction force.

Therefore, without loss of generality, we assume to simplify the model and focus on the effect of the truly important parameters: , , and .

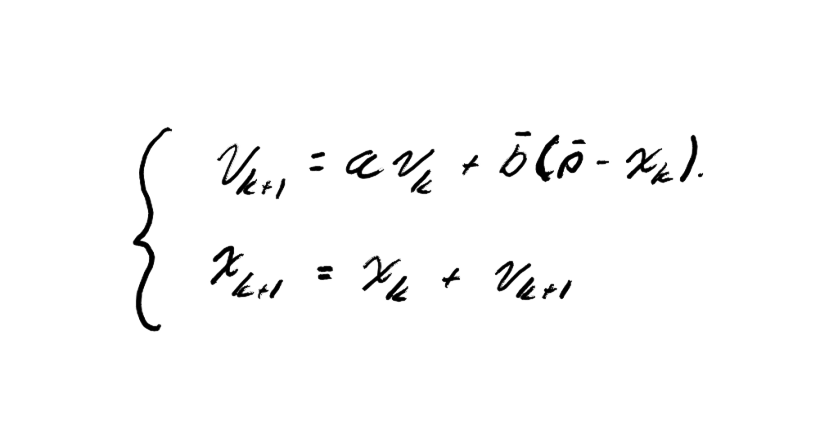

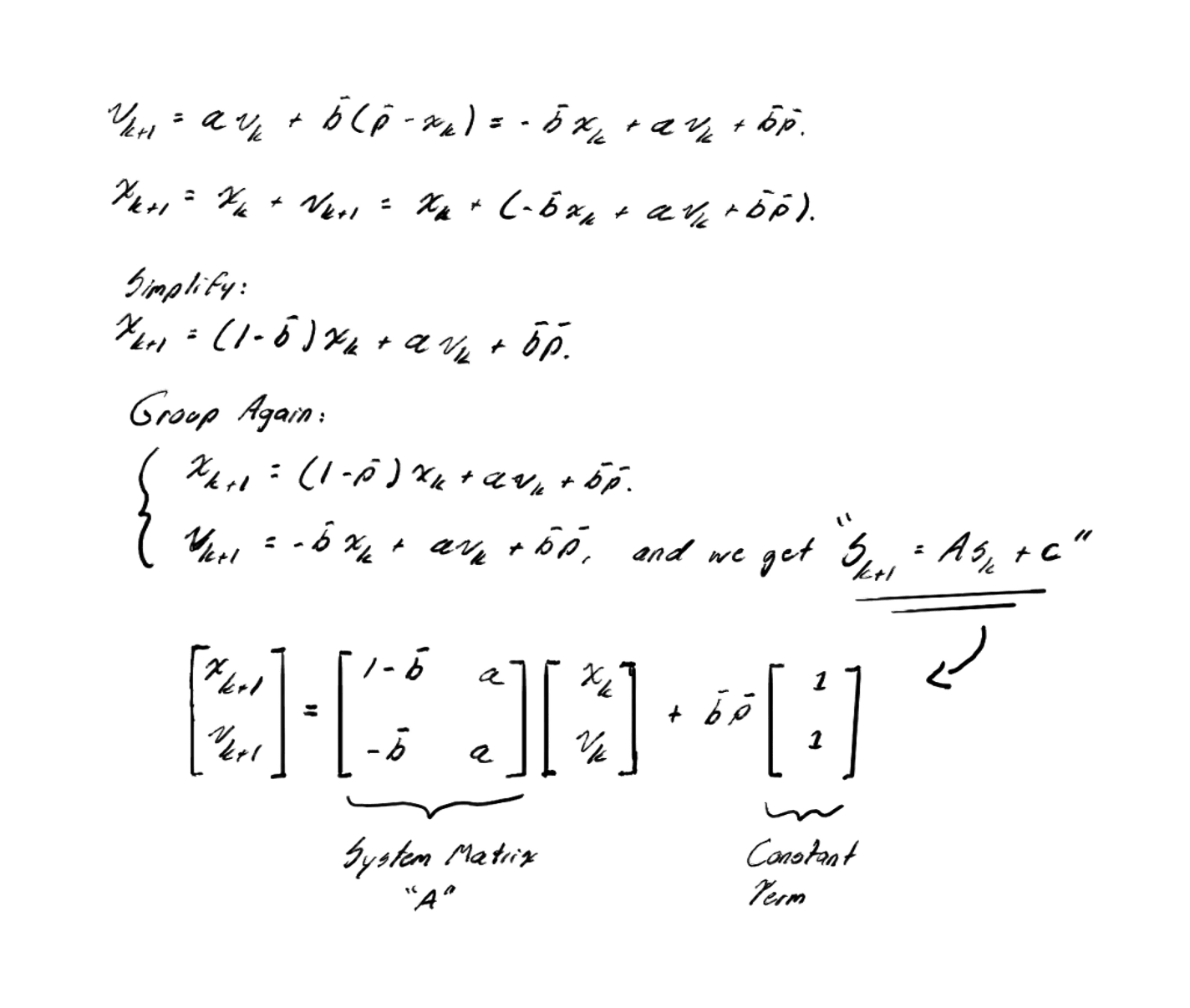

Now that we have eliminated and simplified our system of equations, we can rewrite the original two update equations:

If we group the terms, we can represent the complete system in matrix form as a linear affine system:

In this formulation:

- The matrix describes the internal dynamics of the system: how positions and velocities combine in each iteration.

- The vector acts as a bias (constant term), which can shift the equilibrium point but does not affect the stability of the system.

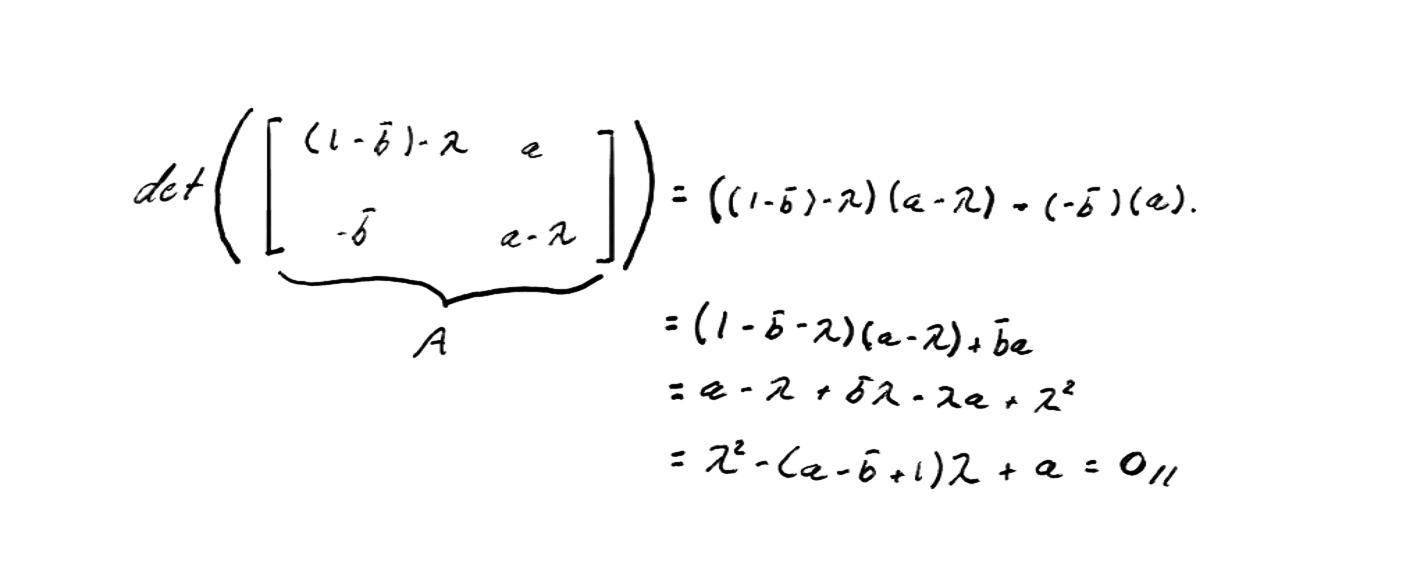

The convergence of PSO depends solely on the eigenvalues of matrix .

According to linear systems theory, the system's behavior is determined by the magnitude of these eigenvalues.

Specifically, the system converges if and only if:

This condition guarantees that, as iterations progress, the positions and velocities of the particles tend toward a stable point in the search space.

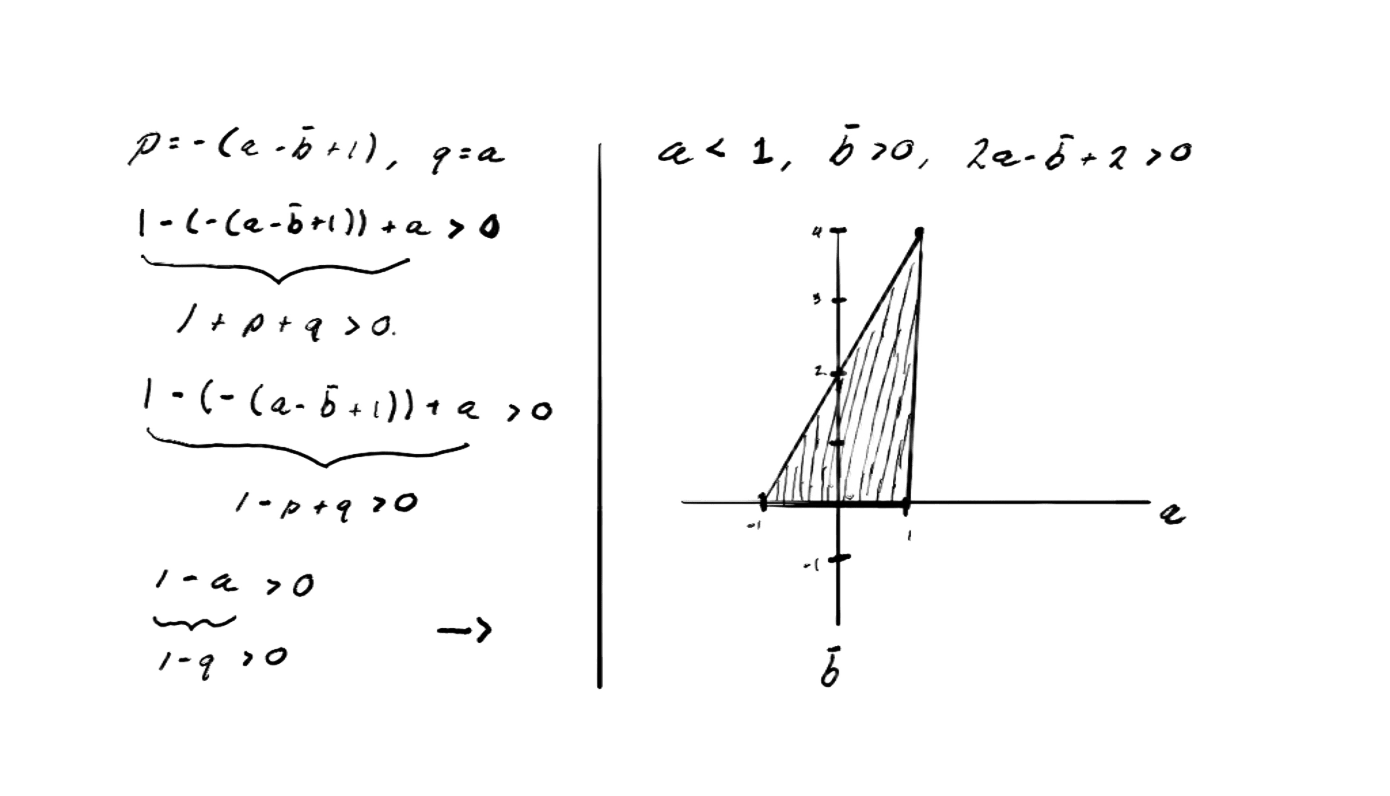

Having our values, our work is to find which combinations of parameters and meet the necessary conditions for the system to be stable and convergent.

For this, we use the Stability Conditions for Discrete Second-Order Systems, known as the Jury Stability Criterion. If the characteristic equation of the system is:

Then, the roots satisfy if and only if the following Jury conditions are met:

These inequalities define the stability region in the parameter plane.

Any set of values that falls within this region (the triangular zone) corresponds to algorithm configurations that converge.

By analyzing these conditions together with the values derived from PSO parameters, we can identify the areas where the system is stable and study how different convergence regimes change according to the chosen hyperparameters.

And with this, we conclude the convergence study of the PSO model.

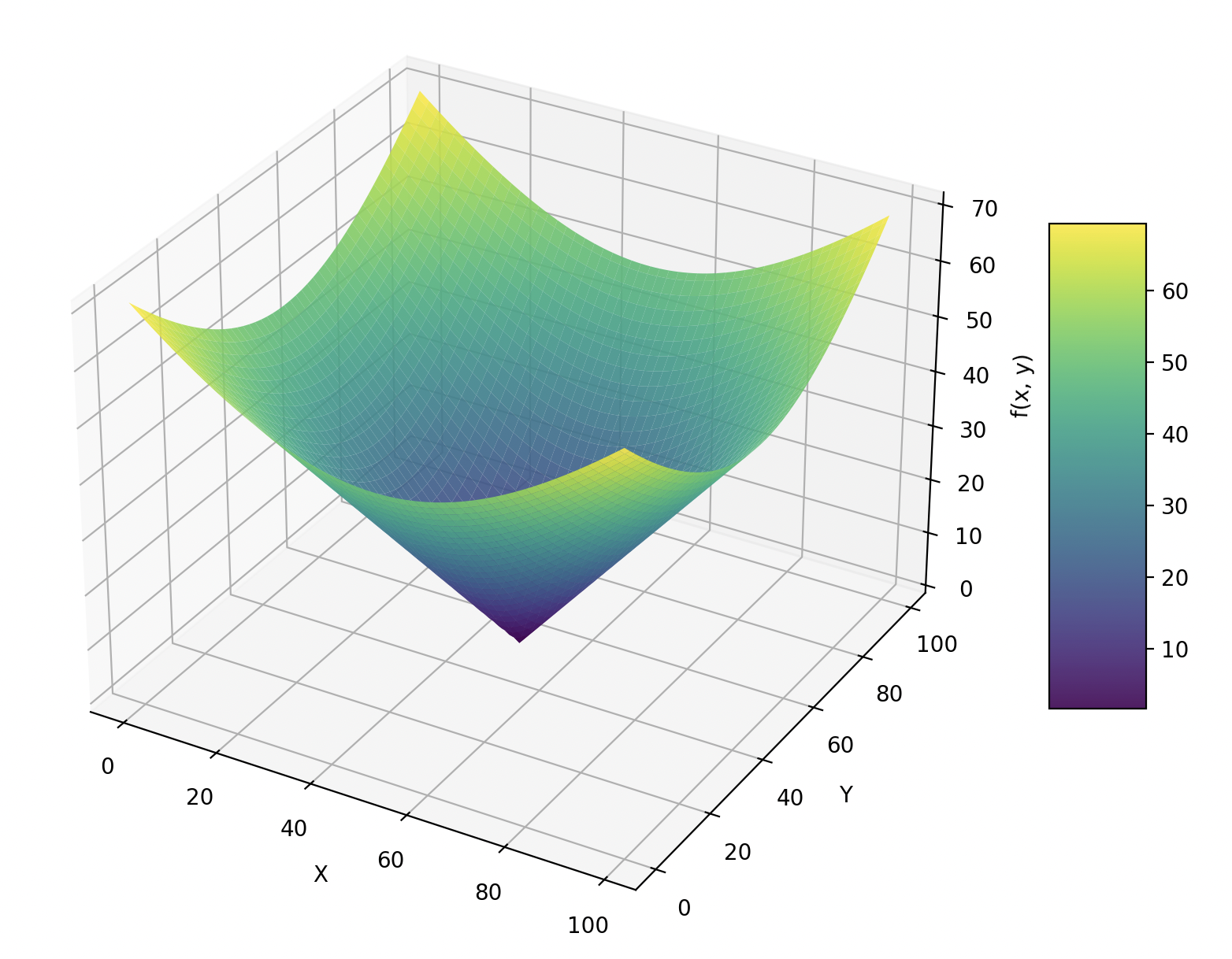

Demonstration

Source Code

Find the complete implementation on GitHub: Particle Swarm Optimization.

Final Reflection

We can see that the algorithm works, and beyond that, it teaches us a different way of thinking about optimization.

This algorithm demonstrates that we can use the principles of nature cooperation, adaptation, and collective learning, to solve complex problems in an elegant and efficient way.

One of the great advantages of this method is that it does not require derivatives to optimize functions. This makes it an excellent alternative to gradient descent, especially in cases where the objective function is discontinuous, noisy, or non-differentiable.

PSO also adapts well to high-dimensional spaces and can work in discrete domains. Additionally, its structure allows for natural parallelization: each particle acts independently, communicating only to share the best global information.

However, it also has limitations.

PSO does not guarantee an exact optimal solution, but rather a very close approximation. And, like any global search method, it depends on correctly defining the initial search space, which directly influences the quality of the final result.

PSO is a clear example of how nature can inspire powerful computational solutions, reminding us that intelligence does not always arise from central control, but from the balance between the individual and the collective.